Showing all 10 results

In his monumental tome from 2007, A Secular Age, Canadian philosopher

Charles Taylor sets himself the task of accounting for the dramatic departure

of modernity from the clarity and cohesiveness of a God-governed cosmos.

Time was, religion was everywhere – was, as Taylor puts it, ‘interwoven with

everything else’. It was virtually impossible not to believe in God, to share in

a cosmic and social imaginary that made sense of everything in terms of God’s

pervasive presence and providence. But then came the ‘disenchantment’.

God ceased to be, for many people, even ‘an eligible possibility’, and where

a religious outlook did survive it provided merely one explanation among

others. Whatever its merit, it was now purely a private matter; there was no

room for it in the public sphere.

There can be no doubt that Ireland lies near the endpoint of the process

Taylor describes. Here, as in most developed world countries, transcendental

values tend not to feature in the dominant perceptions of human flourishing;

the facts and values of the world do not require reference to anything beyond

it. Hence, the ‘immanent frame’, with all its subjectivities, is sufficient. It

follows then that religion has become a private thing, and the public sphere

reflects instead what Taylor calls a culture of ‘expressive individualism’. It

took only a few decades for this to happen. As historian Crawford Gribben

recently put it, Ireland has undergone ‘sudden-onset secularisation’, a

bewilderingly swift transformation of its religious, political and social

culture. The past, even the relatively recent past, is a strange country.

How is this to be understood or explained? Taylor’s grand-theory

description – his charting of the ‘inward turn’ in both religious practice and

the exercise of reason, as well as his account of how transcendent humanism

appeared increasingly problematic – helps explain the conditions which made

the dramatic shift in Ireland’s self-understanding possible. Many Irish people

felt ‘cross-pressured’ (to use Taylor’s term) in the face of the conflict between

Christian orthodoxy and other systems of meaning. The outside pressures

offered by purely immanent perspectives helped to ‘fragilise’ their Christian

beliefs and present them with multiple possible ‘third ways’, intermediate

stances between belief and unbelief.

But what about the pressures from within? What about the fragilisation of

Christian belief in Ireland caused by another kind of disenchantment – the loss

of trust in the Irish Catholic Church as a force for good, the sense of betrayal

as the sordid history of clerical sexual abuse, the collaboration of religious

congregations in oppressive state institutions, and the mendacious cover-ups

by church officials became apparent? A different kind of explanatory model

from Taylor’s is needed to make sense of all this. What is required in the first

instance is a more micro-level scrutiny of Irish society and culture during the

decades of the transformation and a more concrete inspection of how Irish

people today have come to understand what happened to them and where it

has left them. Derek Scally’s recent book The Best Catholics in the World

(Dublin: Sandycove, 2021) is a thoughtful and honest effort to address this

need, not indeed as an academic venture but rather as a journalistic bid to put

together a credible account of a seismic upheaval in Irish society and culture.

For Scally the bid is also personal. The Ireland of his youth was

unquestionably – and no doubt unquestioningly – Catholic, but that identity

and its legacy seem deeply problematic to him now. He writes from the need

to understand how things happened the way they did.

I want to understand how my Catholic past went from rigid reality to

vanishing act – now you see it, now you don’t. To do that, though, I

need to understand how Catholic Ireland rose to glory and shrivelled

up in shame. Until I do that, I cannot have a proper parting. (9)

The answer to the question of how the Church went from glory to shame is

complex, of course, and requires looking at Irish life well beyond the walls

of Church houses and institutions. Scally covers this well. The prevailing

culture, as he depicts it, was indeed one of ‘clerical coercion’, ‘unforgiving

rigidity’, and Victorian values that had been ‘retooled’ by the Catholic

Church; but it was also one of ‘social snobbery’, where the state – and indeed

the population at large – was content to have ‘shame-containment’ facilities

for ‘fallen’ and troubled women, where the moral probity of clerics was taken

as given, and where, when suspicions arose, ordinary people failed to rise

above a culture of deference, conformity, and silence.

The pressing question is how we should, in the present, address this toxic

past. Scally looks to Germany, his home now for more than twenty years, for

guides to the complex business of coming to terms with the past and ‘with

everyone’s role in it’. ‘It took decades,’ he writes for Germans to realize that engaging with their society’s past –supplementing guilt and blame of the actual perpetrators then with

a wider narrative of personal responsibility to remember – improves their society’s present. (284)

He cites the judgement of German thinkers such as Walter Benjamin,

Theodor Adorno, and Jürgen Habermas that ‘owning our past and how we

remember it is a prerequisite for meaningful engagement with past wrongs,

and that critical reflection on a nation’s past is the normative basis for a

healthy democracy’. We could say that, mutatis mutandis, the same holds for

the Catholic Church, both in Ireland and elsewhere. For the sake of a healthy

future, the Church must reflect critically on its past. If it doesn’t succeed

in remembering the injustices it has perpetrated or permitted, in owning

them and keeping the memory of them alive, bearing ‘ethical witness’ to

the victims through reconciliation, restorative justice, and appropriate

memorialisation, it cannot expect to be in a position to prevent comparable

injustices happening in the future.

This judgement, this insight into the critical significance of historical

suffering and injustice, lies at the root of the theological work of another

German thinker, Johann Baptist Metz. Metz engaged extensively with

Habermas, Ernst Bloch, and other critical theorists associated with the

Frankfurt School, and he addressed similar questions to theirs, but in a

theological register. His highly influential political theology, which for him

constituted a ‘practical fundamental theology’, is an elaborate working out

of the theological significance of memory, most especially the memoria

passionis, the memory of the suffering of others:

The whole of my theological work is attuned by the specific

sensitivity for theodicy, the question of God in the face of the history

of suffering of the world, of ‘his’ world. What would later come to

be called ‘political theology’ has its roots here: speaking about God

within the conversio ad passionem.

At the heart of the issue of historical injustice, for Metz, is what Walter

Benjamin called ‘anamnestic solidarity’, a resolute remembrance of those

who have suffered in the past – remembering them against the dominant

narratives, against what Metz calls ‘the conversation of the victors’.

Theology, understood in this way, is always a form of interruption – as of

course was the life and death of Jesus Christ. And it is Christ’s suffering that

signals the emancipatory and redemptive potential of the memoria passionis.

Christ’s redemption cannot be separated from his passion and death. The

future is embedded in the past. The eschatological hope of the Church rests

firmly, then, in the memory of the suffering of Christ, hence in that of all

victims. And so, the memory of Christ is, in a term Metz borrowed from

Herbert Marcuse, a ‘dangerous memory’ – – dangerous because it gives pride

of place to the narrative of an innocent man suffering torture and death at

the hands of those in power, and so keeps alive a commitment to justice and

change. It is, he writes, an anticipatory remembering; it holds the anticipation of a specific

future for humankind as a future for the suffering, for those without

hope, for the oppressed, the disabled, and the useless of this earth.

Christian hope for the future, in sum, lies in remembrance of the victims

of the past and service to victims in the present. A necessary corollary of

this is that Church authority ought not to be exercised as a form of power,

but only, as Pope Francis has repeatedly said, as a form of service. Metz

cautions against ‘locating’ and ‘enthroning’ the ‘God of the passion of Jesus’

politically, whether by a party, a race, a nation, or indeed a church. This must

be opposed and unmasked as idolatry, or mere ideology.

The Catholic Church in Ireland, of course, has been well and truly

‘dethroned’ when it comes to relations with the state. In his epilogue, Scally

recognises that the context for his book is the present-day ‘reinvention of

Ireland’ after it has flipped from a religious to an increasingly secular society.

New terms of engagement have still to be defined, but, Scally writes, ‘if it is

to be successful, it needs to be more inclusive and generous to all – to people

of faith and non-believers – than it was in the past’. More generous too, as

both Scally and Metz would have agreed, to the historical victims of its own

abuse of power.

This year marks the fiftieth anniversary of the removal by referendum

of the mention of the special position of the Catholic Church in the Irish

constitution. In a sense the amendment was largely symbolic, as Ireland

never was strictly a confessional state and the surrounding articles in the

constitution showed a firm commitment to liberal democratic values. Yet

the result did indeed mark a significant shift in Irish attitudes: the Catholic

Church, just like any other Church or faith, would henceforth be a beneficiary

of the secular values enshrined in the constitution, but its teaching would have

no formal bearing on how they were to be interpreted. Most Catholics now

would see this decoupling of Church and state as a positive and necessary

thing. We find in Metz, as indeed we do in Charles Taylor, a sense that the

secularity of the world in recent centuries is not fundamentally opposed to

Christianity, that it is in fact originally a Christian event that has arisen, as

Metz puts it, ‘not against Christianity but through it’.

There are grounds for hope here. There is a common humanistic discourse

that Christians, other people of faith, and those without any faith can enter

into on equal terms, and if good discursive habits are developed Christians

can make an invaluable and decisive impact in a culturally polycentric world

– not by any means free of discord but protected from the worst injustice and

violence by a common regard for human dignity and a respect for positive

political and social norms. For this to happen, though, neither the Church nor

the state can afford to allow the past to be forgotten. Scally finishes his book

with a cautionary tale from Germany. Erich Maria Remarque’s harrowing

novel about the First World War, All Quiet on the Western Front, was a

searing condemnation of the old conservative elite and the utter indifference

of military commanders to the suffering of their soldiers on the front, and

as such it was suppressed by the Nazis. ‘A society blinded by the trauma

of one war,’ Scally concludes, ‘walked into another’. And in July of this

year Pope Francis sounded the same note when he asked forgiveness of the

indigenous peoples of Canada for the sorry history of abuse in the residential

schools: ‘Without real indignation, without historical memory and without a

commitment to learning from past mistakes, problems remain unsolved and

keep coming back’.

Metz is just as admonitory, but his summary of what there is to be gained

by not turning our backs on the past rings a welcome note of hope:

What the memory of suffering brings into political life… is a new

moral imagination with regard to others’ suffering, which should

bear fruit in an excessive, uncalculated partiality for the weak and the

voiceless. But this is the way that the Christian memoria passionis

can become a ferment for that new political life for which we are

searching, so that we might have a human future.

***

The contributors to this issue of Studies were asked to write in response to

Derek Scally’s book, either engaging with it directly or holding it in mind

while developing a related theme. Some of the articles take a diagnostic

approach, examining the nature of the damage and the root causes behind

it, while others look forward to the ways in which the Catholic Church can

address its past and build up a healthier culture for the future.

In ‘Home Truths: Irish Neoliberalism’s Eclipse of Irish Catholicism’,

Kevin Hargaden takes his cue from Scally’s observation that ‘historic,

economic and social circumstances made us subjects of a very particular

type of Catholicism in Ireland’. What specifically set Irish Catholicism

apart? In Hargaden’s view, the Irish Church took its shape from the anxiety

over ‘societal legitimation’ and therefore the ‘pursuit of social and political

influence through economic attainment’, which were inseparable from the

‘devotional revolution’ and Church reform of Cardinal Cullen in the midnineteenth

century. ‘If the capitalist ambition of the emerging middle class

played a central role in explaining the rise of Irish Catholicism’, Hargaden

asks, ‘why would it not play a part in its downfall?’ Applying the insights

of Australian sociologist Melinda Cooper concerning the unlikely alliance

between neoliberalism and neoconservatism, he argues that the sense of

‘family values’ that was enshrined in Irish Catholic life was traceable to

the ‘moral vision’ of neoliberal technocracy. One way to continue Scally’s

work, he suggests, would be to ‘consider the ways in which neoliberalism

has stepped into the space that had been occupied by the church’. That this

transition from the moral legitimation of Catholicism to that of neoliberalism

occurred so smoothly is due to the fact that ‘Irish Catholicism had already

cultivated and cherished these commitments over generations’.

In ‘Surviving the Secular: Faith, Grief, Parody’, Michael Kirwan is

ultimately sanguine about what he calls ‘the Church’s survival into a post-

Christendom future’. The issue, as he sees it, is that it is not just the Church

that is in crisis, but the secular state too. With Charles Taylor he rejects the

‘subtraction model’ of the secularisation thesis: ‘[I]t is simply not the case

that stripping away religion reveals a fully coherent and autonomous (ovenready?)

secular social order’. Rather, secular society lacks the resources to

provide a governing moral vision that establishes binding ideals – the kind of

vision that religions can provide, as exponents of postsecularism affirm. So,

there is an opportunity here for both religion and the secular order. Kirwan

invokes Pope Francis’s image of a ‘polyphonic’ resolution, ‘emphasising

harmony and complementarity’. As for the Church specifically, if it can learn

once again to ‘parody’, to ‘re-work and re-dedicate what it finds to hand in

the surrounding culture’, it may ‘survive and even flourish’.

Whatever shape future relations between Catholicism and the Irish state

takes, it is certain that the priest will never again hold the status that he did

in decades past. John Littleton writes of his own experience of priestly life,

spanning nearly forty years, in ‘The changed Reality of Being a Catholic

Priest in Today’s Ireland’. In the early years of his ministry, the priest enjoyed

social centrality and an extraordinarily high level of deference; but in more

recent years that has all evaporated, and priests have had to learn to be ‘happy

in their irrelevance’ – a phrase which Littleton sees as wise and helpful. Still,

he insists, priests need to remain convinced that they have an important role

in both the Church and in society.

The image of the priest has another significance, however. It lies at the

heart of a perception of injustice in the Church which is still in critical need

of attention. Gráinne Doherty’s essay, ‘Women’s Prophetic Voice for the

Church’, notes a striking disconnect between the lived experience of women

and the Church’s language about them. Specifically, Catholic talk about the

ontological difference between women and men, or about complementarity,

or about ‘feminine genius’, all of which have appeared in the texts of the

last three popes, don’t resonate with women of faith in Ireland. Women are

spoken about as if they were central to the life of the Church, but they are

treated as if they were merely peripheral. Where this shows most starkly is

in relation to sacramental ministry, particularly concerning the Eucharist. For

many women, Doherty observes, the Eucharist is marked by ambivalence:

‘[O]n the one hand, it proclaims a Gospel of justice and equality, but on

the other it is a site of exclusion for women’. She finds grounds for hope

in the Irish Church’s recent experience of the synodal process. This has

given the Church an opportunity to remember that ‘not only is it called to be

prophetic, but it is itself challenged to listen to the prophetic voice of its own

marginalised’.

Two members of the Irish synodal pathway steering committee, Bishop

Brendan Leahy and Gerry O’Hanlon SJ, express careful optimism here that

Pope Francis’s implementation of synodality can succeed in setting the

Church on a new footing, one that would leave little room for the abuses

of power that have blighted the Church in the past. The point of synodality

is to ‘invert the pyramid’, as Francis has frequently said – to undermine the

older power structure by implementing the ecclesiological vision of Vatican

II. The ‘base’, the People of God, are set above the clergy and holders of

ecclesiastical office, whose function it is to listen, to support and to serve.

Francis doesn’t see this as one option among others, or as a tactic for the

present time. Synodality, he has said, ‘fundamentally expresses “the nature

of the Church, its shape, its style and its mission”’. It is a fruit of the renewal

of ecclesiology in Vatican II, and so it is a cause for concern for the Pope

that it is dismissed or disparaged frequently by traditionalist Catholics –

‘restorers’, as he calls them in the conversation he had with the editors of

European Jesuit journals last May, which is published in this issue. ‘[T]

he current problem with the Church,’ he remarked, ‘is precisely the nonacceptance

of the Council’.

In Part I of his essay, ‘Going Deep, Going Forth, Going Together’ (Part II

will be published in the winter Studies), Bishop Leahy sees Pope Francis as

building on the work of his post-conciliar predecessors, taking the next step

in implementing the ‘renewal movement’ by promoting its central themes of

communion, mission, and participation. All of this Francis sees as aspects of a

‘pastoral conversion in the Church’s way of seeing and acting’, instigated by

the council and bearing fruit now in the synodal path. The Church in Ireland

has had to confront the dark chapters of its own history, Bishop Leahy says,

and this has shown clearly both ‘the need to go deeper’ and the importance

of change from below.

For Gerry O’Hanlon (‘The Future of the Catholic Church in Ireland:

Synodality and the Wounds of Abuse’), Derek Scally’s book is of ‘central

relevance’ to reform and renewal of the Irish Church, which is the agenda of

the synodal pathway. Scally warns that if the Church fails to reflect deeply on

the sexual abuse scandal it runs the risk of ‘repeating, unconsciously and in

new forms, the structural flaws of the past’. O’Hanlon concurs. How can the

Church tackle the serious issues of the day, he asks, ‘if we do not understand

what caused the trauma that was clerical sexual abuse in all its forms?’ He

also endorses Scally’s suggestions of practical steps in coming to terms with

our past – setting up museums, institutes of remembrance, memorials, and

the like, but most of all the implementation of some kind of process like a

citizens’ assembly. For O’Hanlon, the synodal pathway performs within the

Church much of the function which a citizens’ assembly would perform in

the state at large. By opposing the clericalism that has often led to the abuse

of power and by inviting all the Church’s faithful to enter into a free and open

dialogue, the synodal pathway presents the Church with an opportunity to

conduct a proper ‘reckoning’, an appropriate coming to terms with abuse in

the Church’s past.

In ‘Christianity for Grown-ups’, Kieran O’Mahony also sees The Best

Catholics in the World as essential reading for people involved in faith in

Ireland. It requires them to try to understand from their own experience what

it was that brought about ‘the cultural collapse of the Irish Catholic Church

as a voice in society’. This, in fact, is something which O’Mahony believes

the synodal pathway has facilitated effectively. It has brought to the surface a

range of views from parishes and dioceses across the country and displayed,

he believes, ‘a powerful desire for further adult faith formation’. Key to the

atrocities perpetrated in the Church and to its general decline, O’Mahony

contends, is the longstanding failure of the Church to provide thorough

catechesis – to give people an adult faith when they were no longer children

– and to help them develop a deep prayer life and ‘a grown-up frame of

reference for what we believe’. Sources of hope for him include the collapse

of Cardinal Cullen’s church and ‘the powerful awakening and ownership

triggered by the Synodal Pathway’.

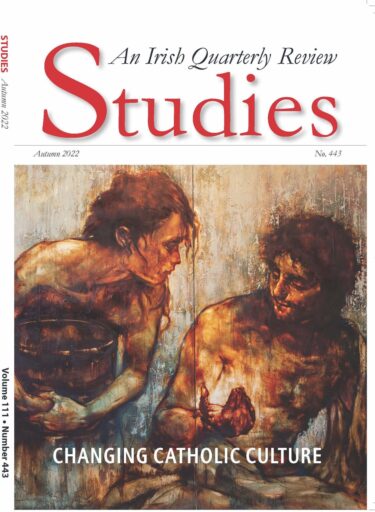

Br Emmaus O’Herlihy’s essay to accompany his extraordinary painting

of the Samaritan woman at the well, which hangs on the wall of the church in

Glenstal Abbey and graces the cover of this issue of Studies, was not requested

as a response to Scally’s book. It is included here, however, because it holds a

message that is germane to our theme. That is, as Emmaus O’Herlihy puts it,

‘that Christianity is founded not on a set of creedal formulations or a logical

system but on the person of Jesus Christ’. What we see in the painting is an

encounter, a deep engagement with Christ at the well. Cor ad cor loquitur,

as St John Henry Newman’s coat of arms has it – ‘One heart speaks to

another’. That it shows a woman leaning in on Christ, not reticent or passive

but forward and almost pushy, also conveys a valuable object lesson. It both

rejects a stereotype which historically has impeded efforts to combat the

exclusion and unequal treatment of women in the Church and it displays

the kind of parrhesia – courageous outspokenness – which Pope Francis has

encouraged and which is essential to the success of synodality.