As we reach the end of the first full week of the new year, and as we’ve been making resolutions for good changes in our lives – we present an extract from Dr Corinna Ricasoli’s 2015 Studies article, “‘Memento Mori’ in Baroque Rome”; a meditation on the funerary art of the 17th century and a culture – both lay and religious – that focused on developing a good life & good death.

Images included in the original publication have been reproduced in the body of this post with their original descriptions. An additional note to readers that translations for less ubiquitous Latin terms have been included in square parentheses. These were not included in the original paper but included by Studies for this blog.

Dr Corinna Ricasoli is a native of Rome and graduated cum laude from Universita degli Studi Roma Tre with an MA in Art History (Early Modern). She is a freelance art historian and museum curator with an international exhibition record, including with the Louvre and the Rijksmuseum. She is the Founder and Chief Research Officer of Archivitaly, a company that provides research services in Italian and European archives and libraries.

Corinna Ricasoli, ‘”Memento Mori” in Baroque Rome’, Studies: An Irish Review, Vol. 104, No. 416 (Winter 2015/2016), 456-467. JSTOR link: https://www.jstor.org/stable/24640795

(…)

The common concern for both a good death and eternal salvation led to the foundation of brotherhoods, which aimed to help people prepare for a bona mors [‘happy death’]. These congregations were strongly encouraged by the Jesuits, first in Rome and later across Italy. Of particular note in Rome was the Congregazione della Buona Morte, founded by the Jesuit General Vincenzo Carafa in 1648. It fulfilled the task of guiding people along the path toward a good death by means of a good life, and through a constant meditation upon death and Christ’s Passion.

Even if this Congregation’s aim was to foster a lifelong ars moriendi [‘art of dying’], or better still, a lifelong ars vivendi [‘art of living’] mindset in order to achieve a bona mors, it was also well evident that fear – namely, fear of dying a bad death – was the common denominator that encouraged the faithful to participate…In this respect, the Congregazione’s motto is particularly significant: quotidie morimur – we die each day.

(…)

Seventeenth-century culture did not see death as taboo. Lingering over the thought of death and its most shocking aspects was not regarded as strange or excessively morbid. The ruthless representations of death’s unpredictability in both art and music, or its effects on the human body show that to be the case. In fact, death was looked at almost with pleasure and it was represented and revealed with straightforwardness and realism. Death was being faced up to as part of everyday life. This familiarity with, and awareness of death and dying, typical of the Counter-Reformation, also explains the birth of many lay associations in Rome that – already since the sixteenth century – dealt with issues connected to death. See for instance the lay Arciconfraternita di Santa Maria dell’Orazione e Morte (founded in 1538), whose aim was to look for, collect and bury the unclaimed, abandoned bodies of those who had died in the city’s rural hinterland and which had often become food for animals. They also took care of the bodies of people who had died in poverty and could not afford a proper burial.

Of course, besides their faith and devotion, the confreres also benefitted from indulgences for each burial or body collection. Indeed, giving these bodies a proper burial was seen as a humility rite, a memento mori, and as a means to expiate their own sins. Similar purposes (and indulgences) may be found among the members of analogous confraternities in Rome. In summary, in seventeenth-century Rome, people’s concerns about death facilitated the diffusion of confraternities to quite a significant degree, especially in terms of lay associations connected to one’s own, as well as to other people’s deaths. The awareness that death was always nigh persuaded people to do all they could to secure the salvation of their souls. The now familiar figure of death had become part of city life in Rome.

We have hitherto looked at the impact of the Counter-Reformation on the way in which people responded to death and dying. But how did this new approach to death reflect upon funerary art?

Funerary monuments dating back to the fifteenth and early sixteenth centuries generally resolved not to show the most horrifying aspects of death, such as the transi [‘cadaver monuments’] associated with medieval tombs. Indeed, Renaissance tombs were designed to reveal the sweetness and peacefulness of eternal rest, and the individual concerned is represented as if asleep. This type of funerary art is not a memento mori but rather a memento vivere, a celebration of a life lived, as if the memorial’s aim was to divert the bystander’s attention from death in order to focus on life and achievement.

However, during the sixteenth century something had changed, especially after the Council of Trent. Death, once a rare representation in Italian sixteenth-century funerary art, had now become a permanent feature. Tombs still portrayed classical elements, such as the temple-like composition and the bust, but a clear symbol of death – the skull – started to appear more frequently below the inscriptions. Funerary monuments now seemed to be designed for the living, as if the deceased’s last action on this earth is to remind passers-by that life is short, that the future is uncertain, and that everything that is not eternal is nihil [‘nothing, nothingness’].

Skulls (and later skeletons) on funerary monuments were being represented with utmost naturalism: indeed the marble used for these sculptures had an ivory tone to recall the colour of a real human skull, the imitation of which went as far as to represent it with some missing teeth, making the whole image very realistic and unsettling. A variation of this motif is the winged skull, which may probably be considered as less realistic, but it is definitely very emblematic, for it adds another disturbing memento to the iconography: the suddenness of death.

But why else did skull imagery become so popular? In order to answer this question, we must once again refer to the Jesuits’catechesis, and the way in which they encouraged the faithful to deploy an actual skull (or a surrogate) that would better concentrate the mind on death during the meditations suggested by the Exercitia Spiritualia. This explains why the skull is almost omnipresent in seventeenth-century art. It is indeed the subject of many transience-themed paintings. Moreover, all the most important saints depicted in Counter-Reformatory art have been represented either holding a skull or with the skull next to the crucifix and the breviary. See, for example, the many paintings depicting Sts Jerome, Mary Magdalen, Francis or even Carlo Borromeo: in these works, the skull is always present, as it is connected to meditation, and particularly to meditation on death and human transience. Hence the skull is a symbol of contemplation, of spiritual elevation and, ultimately, of sanctity. Also other bones (besides the skull) may be found in paintings that focus on themes of transience. Indeed, there is no need for the skeleton to be complete for it to have a strong symbolic effectiveness. Even if in fragments, every bone of a skeleton recalls death in the same powerful way, just as the objects to which skulls (and bones in general) are usually conjoined, such as the scythe and the hourglass.

In the seventeenth century, the image of death in funerary art developed further and the skull was increasingly replaced by the entire skeleton. Often, death is also represented as a (winged) skeleton holding a scythe – clearly a medieval revival of the iconography of death. Thus, the medieval gruesome rotting corpse of the transi has been replaced by the ‘clean’ and ‘anatomical’ skeleton, also called morte secca, which is now a simple symbol of one’s finis vitae [‘end of life’].

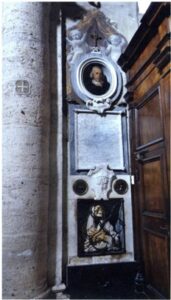

Examples of the clean skeleton may be found both in the tomb of Mariano Pietro Vecchiarelli in the Roman church of San Pietro in Vincoli, whose portrait is supported by two skeletons, and in the tomb of Giovanni Battista Gisleni in Santa Maria del Popolo (1672). The latter is a quite simple memorial designed by Gisleni himself. It is divided in half by an inscription: above it there is Gisleni’s portrait, while below it there is a half-length shrouded yellow marble skeleton, arguably Gisleni’s portrait post mortem. Although the first portrait depicts Gisleni as quite alive, the cartouche below it reads neque hic vivus, i.e. neither living here. Conversely, the cartouche below the skeleton reads neque illic mortuus, i.e. nor dead there. So, Gisleni’s portrait reveals the illusion oflife – the real dead person is he who looks alive; whereas the skeleton (the dead Gisleni) tells us that even if dead he is in fact living because, on a salvific level, not being alive does not mean that one is not living anymore.

The hope for the immortal life of the soul is juxtaposed with the unsettling reality of the nothing: everything, including human existence is nothing, because it is bound to vanish and be forgotten. It is some sort of nihilism ante litteram, which is present – more or less manifestly – in almost every funerary monument in seventeenth-century Rome. See, for example, the tombstone of Cardinal Antonio Marcello Barberini in the Church of Santa Maria della Concezione dei Cappuccini, which reads Hic iacet pulvis, cinis et nihil – Here lie dust, ashes and nothing, or the grave of the Altieri (husband and wife) in Santa Maria in Portico in Campitelli of 1709. Their tombs face each other on opposite sides of the chapel. The most interesting aspect of these tombs is the inscription itself that, on the bare tomb of the husband only reads nihil, while on the wife’s tomb reads umbra. Nothing and shadow: these are two terms and concepts that are very popular in the baroque cultural mentality, as they obviously recall the well-known idea of human life being elusive and fragile like a shadow or a dream. In some tombs in Roman churches, the skeleton is replaced by an allegory of Time, usually represented as an old man…

…This interchangeability between death as a skeleton with an hourglass and death as an allegory of Time in seventeenth century Roman memorials (and beyond) deserves brief discussion. The hourglass is obviously associated with death, as it is an iconographical attribute of Time, and it ‘offered a very dramatic symbol of time coming to an end insofar as the individual mortal was concerned’.

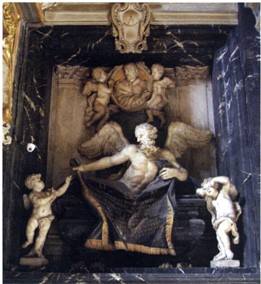

Vice versa, the allegory of Time is often used to symbolise death…Of course, if compared to the iconography of death, the allegory of Time is not as frequent, possibly because of its non-Christian roots (in that it is linked to Chronos). One of the most impressive and well-known examples of death holding an hourglass rather than a scythe is Bernini’s tomb of Alexander VII at St Peter’s in Rome (finished in 1678), which Panofsky considers as the pinnacle of funerary art. As is well known, Bernini had to face the issue of placing the funerary monument on top of an entrance, which made the sepulchral design rather problematic, as the door occupied an awkward position in the middle of the space devoted to it.

Italy)

In order to overcome this problem, Bernini resorted to the classical imagery of the door as a gateway to death, which is common iconography in some Roman sarcophagi. The tomb of Alexander VII represents the Pope praying on a pedestal from which a billowing drape falls down. But the hour of the Pope’s passing has arrived: the skeleton-shaped winged figure of death that seems to fly out of the door reaches out indicating the hourglass, to symbolise the fact that death surprises all people in the midst of their earthly existence. Bernini’s allegory of death shaking its hourglass evidently represents the question of whether an individual ever finds him or herself truly ready to die and face God’s judgement. But the devout figure of the Pope shows that he is not perturbed by death’s sudden arrival, for he has long awaited ‘our sister corporal death’, to put it in St Francis’ words. In short, during the Seicento, the allegory of Time sometimes takes over the duties of Death, possibly because Time, as opposed to Death, appears as less forbidding. However, the allegory of Death as a winged skeleton holding an hourglass is far more common.

By looking at Roman funerary monuments dating from around the 1550s onward, it is clear that a change in the way in which people thought about death was under way, especially if we compare these memorials to ones dating back to the early Renaissance. Certainly, the Counter-Reformation and Jesuit catechism and proselytism in Rome were crucial in the process of an alteration in the cultural mentality because, as we have seen, the Jesuits strongly encouraged people to meditate on their own death by fostering attendance at the meetings of the Congregazione della Buona Morte…The iconography of the funerary art of this time and place only further demonstrates this omnipresence of death in the life of seventeenth-century Romans.

Skulls, skeletons, and hourglasses are a constant presence in Baroque funerary monuments in Roman churches. An awareness of human transience is relentlessly evoked, and the consciousness that the nature of earthly and bodily existence is as nothing, is also visible in tombs, inscriptions and decorations, where the words nihil and nemo are frequently included. In a city where this nothing is everything, and where death’s claw strikes down all that is worldly, hurling it into oblivion, the temptation to assume that there may really be nothing even beyond death may have become extremely strong. Human beings are bound to become cinis, pulvis et nihil and to sink into oblivion, but whereas there is nothing a person can do to avoid this fate, a funerary monument might forestall oblivion by securing the memory of one’s passage through this world.

(…)